Digital Museum Records: The WDM and the National Inventory Project

Curatorial & Corporate Services Centre

January 12, 2026

Categories:

By Kaiti Hannah, Curatorial Associate

Recordkeeping is a vital part of museum collections management. Before computer-based databases, keeping, updating and referring to artifact records meant manually sifting through files and card catalogues to find information.

Digital databases dramatically changed the ways artifact records could be accessed. Searching for keywords, dates or names could bring up a list of every relevant artifact in moments, saving the time it would take to manually sift through dozens of files.

The WDM’s own digitization efforts began in the 1970s, when we joined the National Inventory Program, a Canada-wide effort to create a database of artifacts held in museum collections across the country.

The National Inventory Project

In 1972, planning for the Canadian National Inventory Program (NIP) began. Run by the organization now known as the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN), the goal of the NIP was to create a centralized, digital database of museum collections across Canada. The first four museums to participate were the four national museums in Canada: the National Museum of Man (now the Canadian Museum of History), the National Gallery of Canada, the National Museum of Science and Technology (now Ingenium), and the Museum of Nature.

The goal of the program was “to create an inventory of the cultural and scientific collections held by public institutions in Canada. This idea was an integral part of the new National Museum Policy of decentralization of recourses, announced by the Secretary of State in 1972.”[1] The plan was that eventually museums would have computer terminals on their own premises which they could use to look up their own collection records, while the records of all the participating institutions would be centrally available for look-up in Ottawa.

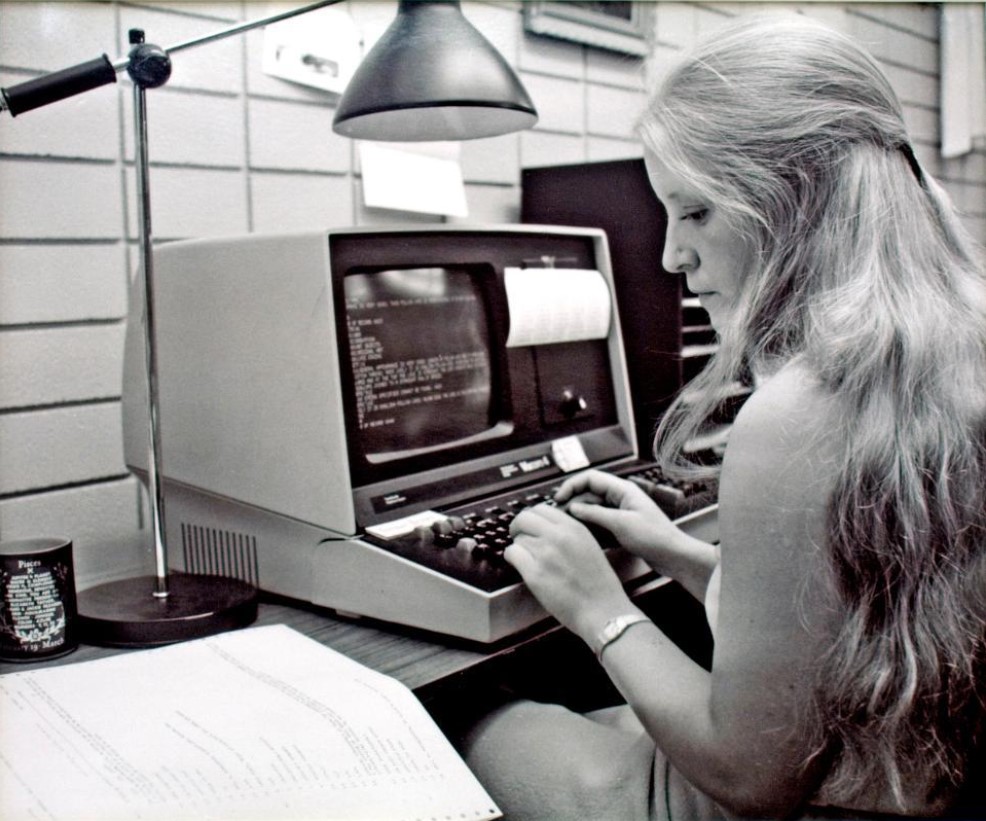

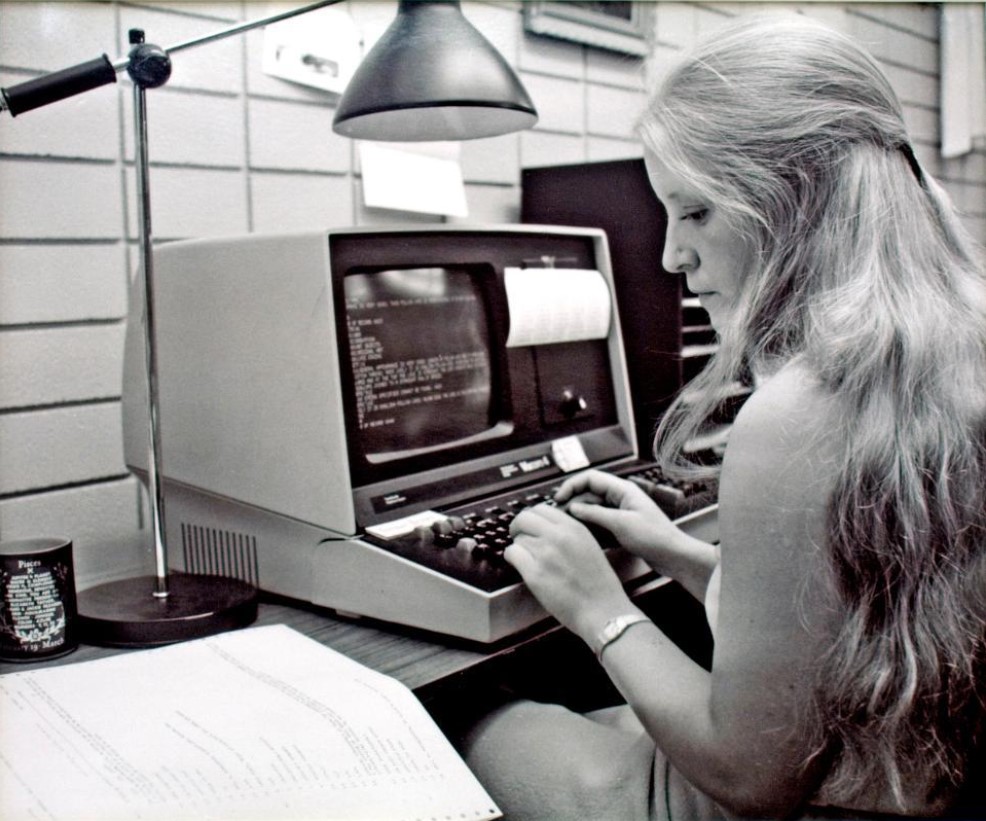

The NIP had to create software programs to track these artifacts from scratch. They created two separate systems: one to enter information and one to retrieve information. Because computers were not yet widely-used, were very expensive, and required very large storage spaces, few museums had access to a computer they could use to input their own artifact data. Instead, museums mailed documents with the necessary information to Ottawa, where they would be entered into the database by NIP staff.

In its first 5 years, 52 institutions across Canada joined the program and 400,000 objects were documented in the database. 20 institutions, including the WDM, had computer terminals installed locally by 1978. These computers allowed museums to enter data themselves, which would then be saved to cassette drives and mailed to Ottawa to be added to the database.

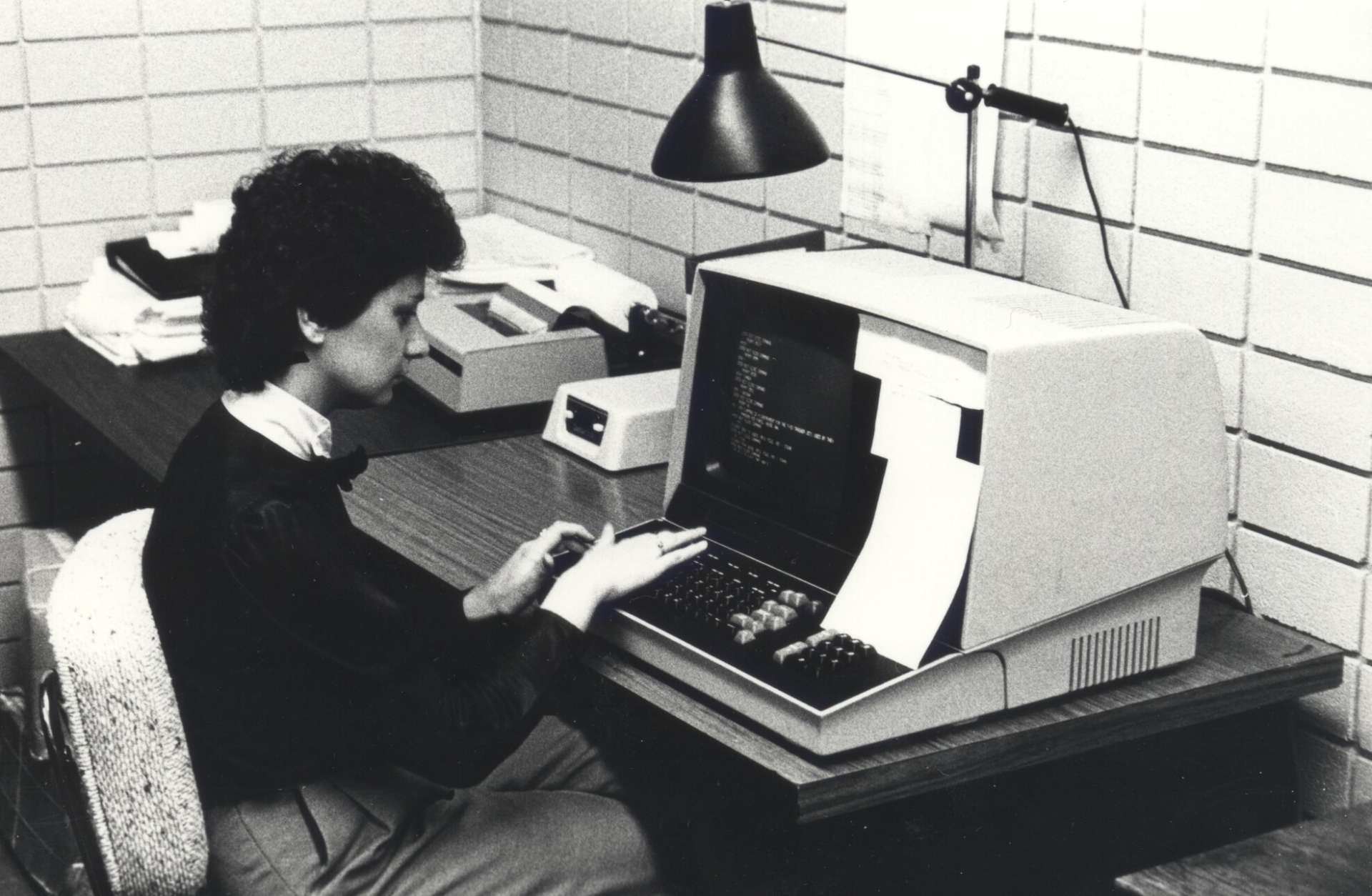

In 1982, the NIP launched a new Collections Management System (CMS) to replace the NIP. The new program was called PARIS (Pictorial and Artifact Retrieval Information System) and the NIP was renamed Canadian Heritage Information Network.

By the mid-1980s, the network included 75 computer terminals across Canada. It was also around this time that the internet began to allow museums to transmit data to Ottawa digitally. “Staff used computer terminals or micro computers to communicate directly with the system by telephone or by dialing into the DATAPAC network.”[2]

By the 1990s, CHIN was shifting its priorities away from collections management services to focus on broader heritage activities, and in 1995 they decided to stop offering collections management services completely.

The NIP was innovative for its time; it was the first online national collections database open to the public anywhere in the world. The program helped standardize data fields and terminology used in museum records across Canada and helped bring Canadian museums into the digital age.

The NIP also made it easier for museums to keep and maintain more robust records on their collections. When describing the project’s first five years in 1978, Peter Homulos explained, “With much of the clerical work now associated with the maintenance of museum records eliminated, museum staff will have more time to address the problem [of poor documentation]. Professional staff can concentrate on researching and preparing the information which makes up the master record; all further cross-reference and summaries can be done by computer.”[3]

The WDM in the NIP

The WDM had joined the NIP by 1975 as one of the earlier participants in the program. At first, catalogue cards with all the artifact information were mailed to Ottawa to be entered into the system, but once they switched to PARIS, WDM staff were able to input data locally. In 1982, CHIN flew six WDM staff members to Ottawa for a one-week training session on PARIS.

There was a steep learning curve for the staff members who went to Ottawa for training. Even just the experience of typing information on a computer was different from filling out paper records by hand.

When the WDM began creating digital records locally, many different staff members could have been able to create records. However, in the interest of keeping records as consistent as possible, the decision was made to make one person responsible for all the entries.

The Data Entry Operator had a quota of entering 50 catalogue cards a day into the computer. She was the only person who had the ability to enter data; WDM locations had the ability to do searches on the database but could not enter or change any information.

When CHIN ended their database program in the 1990s, the WDM had to seek out a new database to use. Museum staff looked at many different program options before deciding on Virtual Collections (VC), the same system the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon was using at the time. It had been developed by a Canadian company that had never handled a collection as big as the WDM’s, but they agreed they were willing to take on the challenge. CHIN migrated all of the WDM’s data to VC in 1997.

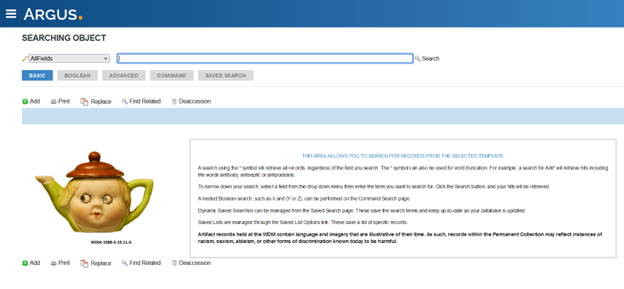

The Virtual Collections software stopped being supported by its vendor in 2014. It could still be used, but there would be no updates or support. In 2018, the WDM began the process of selecting a new Collections Management System to replace VC. After hearing pitches for numerous different systems, the WDM settled on Argus, a program by Lucidea. Argus was chosen for a few reasons. One of the biggest appeals was that it is browser-based, so it can be accessed from any computer with an internet connection. It also allows for a publicly-accessible side, where anyone can look items up while keeping confidential information such as donor contact information private.

Museum work as it is done today would be impossible without searchable digital artifact records. Of the 200-300 research inquiries the WDM receives a year, almost 75% of them require searches on Argus to answer. Finding an answer to a question about an artifact might only take a few minutes today, but without a searchable system, it could take hours or days of digging to find what someone is looking for.

Footnotes

[1] Peter Homulos, “The Canadian National Inventory Programme,” Museum International 30, no. 3–4 (September 1978): 153–59, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0033.1978.tb02131.x, 153.

[2] Canadian Heritage Information Network, “Artefacts Canada Technology through the Years: The National Inventory Programme” (Ottawa: Canadian Heritage Information Network, n.d.), 1980s subheading.

[3] Homulos, “The Canadian National Inventory Programme,” 158.