A Saskatchewan Story

Indoor

Saskatoon

A Saskatchewan Story

Celebrate A Saskatchewan Story! Check out a few highlights of this exhibit below.

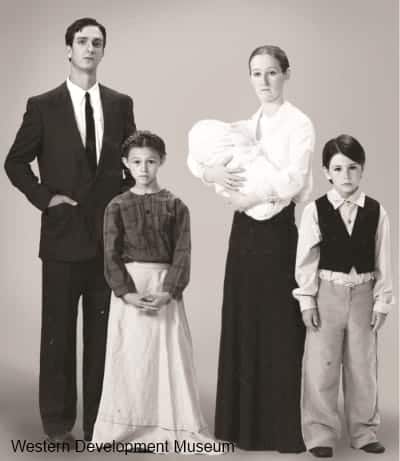

Meet the Worthys

Ride along with the Worthy family as they travel on a train to Saskatchewan in 1905.

What was it like to step off the train carrying your worldly belongings in a few small trunks, your children clutching tightly to your skirts? Will your husband be there to meet you as he promised? You’re exhausted after a two thousand mile train trip. How long will it take to go the fifteen miles to the homestead? What will it be like? A thousand questions tumble about in your brain as you step onto the station platform.

This 21,000 square foot exhibit traces a representative settler family’s journey through 100 years of Saskatchewan history, from arrival at the turn of the 20th century to the present day. Follow the family’s generations as each of them face the challenges of farming in Saskatchewan.

Sod House

At the sod house exhibit, the season is early summer. It is the first summer on the homestead for the farm wife and the children, the second for the husband. In the distance behind the house are storm clouds and smoke from a prairie fire.

Inside, the house measures 3.7 metres (12 feet) by 6 metres (20 feet). Around the house is an outhouse (in the mural), a wood pile and a well.

This house was built by Museum staff using photographs of sod homes to guide them. The sods were plowed from the edge of a slough near the Western Development Museum in North Battleford. It took more than 350 sod blocks to build this house.

First World War

On August 4, 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. This meant Canada, too, was at war. Canadians joined the armed forces in large numbers. Many of these volunteers were Saskatchewan farmers. Women, children and the unemployed stepped in to run the farms. In 1915, Saskatchewan harvested the largest crop in the province’s short history.

Canada’s allies needed wheat. As the price rose, more and more land was seeded to wheat. In 1917, the federal government created a marketing body to control the sale of wheat and fixed the price at three times the pre-war price. But prices for farm machinery also went up and the wages for agricultural labourers doubled.

In 1917, the federal government introduced conscription or compulsory military service because more men were needed on the front. Farmers, however, were granted an exemption because their work was essential to the war effort. By the end of the war on November 11, 1918, Saskatchewan had contributed over 40,000 men to the war effort. Nearly 5,000 had died.

After the war, many veterans returned to their Saskatchewan farms and tried to pick up their normal lives again. But would any of them ever forget the horrors they had seen in the trenches of north-eastern France?

Spanish Flu

Neighbours shut their doors to neighbours, children watched their parents die, coffins piled up, waiting to be buried – the Spanish Flu struck with speed and cruelty.

Infected soldiers returning from the First World War in Europe brought the virus to Canada. In October 1918, it reached Regina and in the first three months of the epidemic, 3,906 people died in Saskatchewan.

The flu began like a cold with sneezing and coughing, then attacked suddenly with pain and chills. Pneumonia set in and death occurred soon after. Young adults between the ages of 20 and 24 were hit hardest.

With few hospitals in rural areas, communities set up emergency hospitals in schools, churches and hotels. Many people had to cope with the disease on their own. They wore gauze masks in public and tried influenza cures such as eucalyptus oil. Prohibition had been in effect since 1916, but many turned to a mickey of bootlegged brandy to fight the flu.

The Spanish Flu epidemic changed rural health care. Communities mobilized to build their own hospitals, and courses on child care and care of the sick were offered to farm women.

In Saskatchewan, 5,018 people died from the Spanish Flu, slightly more than the number of men from Saskatchewan who died in the war.

Eaton’s Catalogue House

See the brand new Eaton’s Catalogue house the Worthys ordered in the 1920s.

Ordering a house through a catalogue … Nonsense! It wasn’t nonsense in the early years of the 20th century. Mail-order house packages from T. Eaton and several other companies were a good option for those farm families who lived miles away from the nearest lumber yard. Winning the Prairie Gamble features partial replicas of a home plan ordered through the Eaton’s catalogue – the Earlsfield model, the most popular style built on the prairies during the late teens and early 1920s.

The Earlsfield first appeared in the 1912 spring and summer catalogue, at a list price of $696.50 plus the cost of freight from Winnipeg. By 1916 it was called the Modern Home and the cost had risen to $887.50. The addition of indoor plumbing cost another $150; heating was $90 extra.

Dozens of Earlsfield houses still stand on the prairies today. In 2005, the WDM salvaged materials from an Earlsfield house on the Miller farm south of Cut Knife for use in the Winning the Prairie Gamble exhibit. The house was built by Norman and Bertha Stewart sometime around 1919. The Stewarts farmed until retiring to Wilkie in 1944. The house was never occupied after that. Years of dust, dirt and grime accumulated. One of the salvage crew remarked, “I can’t explain why such a dirty and uncomfortable job was so much fun, but it was. There was a mysterious exploratory element to it which is hard to put a finger on. There is something very satisfying about saving and recovering real history.”

The old Earlsfield house on the farm near Cut Knife was subsequently demolished, but its original doors, windows, stair fixtures, furnace grates and baseboards have a new life at the Western Development Museum in Saskatoon.

1920s Town Fair and Fun House

Many families like the Worthys saw prosperity in the 1920s. Tag along as they go to the town fair. There’ll be lots to see – new machinery, baking, handiwork and garden displays.

Don’t forget to visit the Fun House! Stare at your reflection in the hall of mirrors and watch your step around the corners!

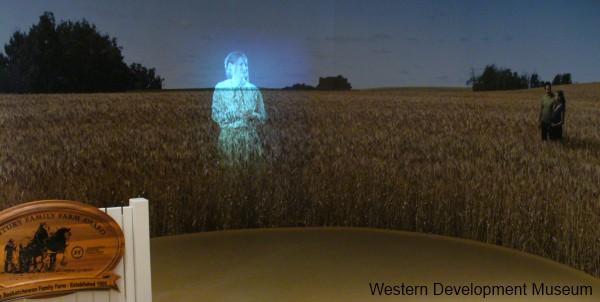

1950s Agriculture and Beyond

Through multi-media presentations, the exhibit explores the technological and scientific revolution and its impact on agriculture and the family farm. New tillage methods, new machinery, agricultural chemicals, exotic livestock, changes in grain transportation systems and marketing, agri-business, research and development, larger farms, declining rural population, agricultural biotechnology and subsidies for farms in times of crisis are some of the themes developed.

Plus, hop into a modern day combine cab to get a farmer’s view of the field and play “Guess the Crop.”

Then, look back at the Worthy family journey with Mrs. Worthy and hear what she thinks the future of the family farm will hold.

Road to Medicare

Saskatchewan has a long tradition of caring for the sick and the elderly. From the farm women who campaigned for improvement in rural housing and health, to the Saskatchewan Anti-Tuberculosis Commission which pioneered the testing of school children for the disease, to the first government-operated air ambulance service in North America in 1946, to the provision of free treatment for cancer patients, to the implementation of Medicare in 1962, Saskatchewan has been a leader on the world stage in providing quality treatment at no charge to all residents.