Historical Research at the WDM

Curatorial & Corporate Services Centre

August 7, 2025

Categories:

As a human history museum, our research methods are rooted in best practices in traditional archival research, in new and emerging standards in community-engaged scholarship and in exciting advances in museology. We cite our work using Chicago Style notes, but we tend to keep that behind the scenes for ease of visitor reading.

Indeed, a lot of what we do in the Curatorial Department happens behind the scenes. We like to talk about how museums are like icebergs – that what you see on the outside of the iceberg, like exhibits and programs, takes a whole lot of work behind the scenes. So, if you’ve ever wondered about what’s it like to work in a history museum, we’re here to shed some light on that.

Our small but mighty research team of seven permanent Curatorial Department staff has a combined dozen History or other humanities degrees, from Bachelor of Arts to Masters to Doctoral level training in History, as well as other undergraduate and graduate degrees and designations in Museum Studies, Public History, Fine Arts, Conservation and Cultural Heritage with a combined 75+ years of experience working in museums. This experience set doesn’t include our students and interns who work with us through Young Canada Works programs, placements from university and college programs across Canada, and as volunteers.

We thought it might be interesting to share some of our recent research and the fascinating primary sources and artifacts we’ve worked with, while developing our newest exhibits, renewing some of our old ones, and assessing our collections. We invite you to think about the research that went into that new exhibit that you see at your WDM location, or when you read the latest edition of Sparks newsletter.

From the Chief Curator – Director of Collections & Research

History-Making in A Provincial Museum

One of the best parts of my job, besides getting to work as a professional historian, is working with the WDM’s incredible team of history-makers in the Curatorial Department. The Curatorial Department staff have shared here some of the ways they practically apply historical research methods in their daily work for the Museum. I hope our readers find it interesting to learn about all the ways we apply research principles in working with artifacts, in exhibit development, and in service to Saskatchewan people in their heritage efforts.

In my role as Chief Curator of the WDM, I am fortunate to work with over 75,000 artifacts in the Collection and to keep up with the latest in Saskatchewan History, whether it’s reading the newest book releases in the field, or connecting with other prairie historians at a lecture. Foremost is my job to create new and engaging exhibits for our visitors, and update existing ones, incorporating the exceptional new research in Prairie History from the last several decades.

Much of my work since joining the Museum almost ten years ago, is focused around responding to the Calls to Action for museums in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report. As such, many of the projects I’ve had the privilege of working on have showcased historical themes in Saskatchewan History that amplify and affirm Indigenous perspectives on our shared past, like the 2018-2022 project Wapaha Ska Oyate: Living our Culture, Sharing our Community at Pion-Era, 1955-69 on permanent exhibition at the WDM Saskatoon. Starting as a photographic naming project with community Elders and Knowledge Keepers from Whitecap Dakota Nation, the project grew into a community-engaged oral history and exhibit project to showcase Dakota history at the WDM once again. Community Elders generously shared oral histories about participating in the WDM’s Pion-Era summer heritage show in the 1950s and 60s. The Late FSIN Senator and Elder Melvin Littlecrow, who co-curated the exhibit, revealed a more complex understanding of Indigenous participation, agency and self-determination in heritage shows like Pion-Era in the mid-20th century prairies. This ground-breaking contribution was shared though the exhibit as well as blogs, conferences and Whitecap community events, and was published in the Summer 2022 edition of Prairie History. It was awarded the Museums Association of Saskatchewan’s Award of Merit in 2023 in recognition of these efforts in co-curation.

Like many museums in Canada with Indigenous collections, we sometimes know little about the cultural belongings in our Collection. This is due to several factors, one of the main reasons being the separation that occurred between origin Indigenous nations and their cultural belongings at the end of the 19th century and through the first half of the 20th, during a time of colonial duress. One such belonging in the WDM Collection is a beaded saddle and saddle pad (WDM-1986-Y-6) believed to have been made by a Métis maker in the Yorkton area, c. 1900. When we have little to no maker provenance on an artifact like this, being creative about the research process is important. In the case of the beaded saddle and saddle pad, we know a lot about the non-Indigenous people who came into contact with it over many decades, including those who owned and cared for it and eventually donated it to the WDM in 1986. Piecing together their stories, using Canadian census records, land records, family histories and local history books, has placed the saddle’s likely origin in the southeast corner of the province as part of what was the giving of a gift or payment for goods about 100 years ago.

The colonial records only take you so far. It is essential to work with Indigenous communities who wish to share their knowledge about cultural belongings like the saddle and pad as the keepers of that history. Working with Métis historian Dr. Cheryl Troupe from the University of Saskatchewan has connected us to some of the area’s Métis Elders who have made suggestions about who else we should talk with to identify the beadwork. We also installed outreach panels about the project at Batoche National Historical Site to garner community-based interest, and hope to jog some memories there. These creative research methods, we hope, will one day identify a probable maker or origin community for the saddle and pad. In the meantime, the saddle is on display at the WDM Yorkton with this new interpretation, showcasing the ways we are sharing more Indigenous perspectives though the Museum.

Another research, writing and curating project I have had the privilege of working on is the J. Marjan Shoe Repair Shop [Brick Building] exhibit at the WDM North Battleford in the Heritage Farm and Village. This exhibit project required mostly traditional historical research, but I also got to connect with the material culture of the artifacts in ways that felt new and fresh. I dove into the file material, family oral history and archival research (particularly in the City of North Battleford Archives) to build the story, the narrative that you can read inside the building when you visit. I had students help with this project over the years as well, piecing together Jakob Marjan’s story using the Canadian Census, local histories, city maps, phone directories and newspapers. The real highlight of this project, though, besides sharing Jakob’s inspirational story and working with his lovely family, was connecting with his artifacts. We are so lucky to have some of Jakob’s shoe repair tools in the WDM Collection, the ones he used every day in his shop from 1932 to 1979. Holding things like his pliers, awls, pincers, edgers and knives connected me to him in a way that you can only find in a museum collection. Jakob held those tools in his own hands for decades, fixing thousands of pairs of shoes and boots along the way, literally leaving his imprint on his past.

Like any historian, I will always love getting lost in reams of historical documents and photographs in the archives, but working with the material culture that reflects our province’s rich and diverse history is such a tangible way to connect with the people whose stories I’m entrusted to tell – it is truly an honor and a privilege.

From our Research Associate

Working Respectfully with Sacred Objects in the Collection

The WDM always tries to ensure that we’re doing our best to give appropriate consideration and respect to the objects that come from a variety of traditions and cultures in our collection. I started thinking about the need for more detailed guidance in some our own records after learning from an archivist about church closures and the specific rules guiding the use, re-use and disposal of sacred objects for a regional diocesan archive. With the support of our Chief Curator and our Collections Manager, our Curatorial Associate and I started a community-engaged research project to begin addressing this need.

Our project focused on objects in artifact storage in Saskatoon due to COVID-19 restrictions. We identified 180 items representing six different spiritual or religious traditions. Then we reached out to those communities to seek out community-based experts. We wrote a cover letter to accompany lists and photographs of the items to send out. The Curatorial Associate was the direct point of communication with the community-based experts, establishing a rapport with and regularly following up with them. The WDM is incredibly grateful for the time and knowledge they shared.

The first and most important task with the experts was to confirm whether the objects we identified were sacred, not sacred, or another category defined by the expert’s community and traditions, and whether it was appropriate for the museum to have the object. We also recorded guidelines from the community experts on what was appropriate and what to avoid for display and storage of each object. This project also allowed us to document who is an accepted authority within each community to be able to reach out for more guidance in future.

From our Curatorial Associate

Helping Others Connect to Research

In my role as Curatorial Associate, I do a lot of historical research. For writing exhibits and website content, I use both primary and secondary sources to learn about a topic, and spend a lot of time corresponding with archives, libraries and other museums for these projects, as well as referring to our own extensive reference collection of books, photographs and archival documents.

But another part of the research I do, in my day-to-day work, is helping members of the public with their research inquiries. The WDM receives over 200 research inquiries a year on a diverse range of topics. Some of the more common requests come from people who are restoring antique farm machinery and are looking for relevant manuals or parts lists to help in their projects; people looking for more information on an artifact or photo they saw in the Museum galleries or online; people who are looking for archival photos for art projects, publications or websites; and people who have found mystery items in their houses or at antique stores that they hope we can help identify.

Looking into these questions often takes me into the WDM’s George Shepherd Library, which holds over 500,000 books, photographs and archival documents. From our collections of Eaton’s catalogues and farm machinery manuals, to flight logs for some of the aircraft in our Collection, there are a lot of sources to refer to.

Most of our library and archival materials are not catalogued digitally, which means we can’t search them on a computer. Some materials have hard copies of basic finding aids or indexes with them, but often locating materials is a matter of knowing where to look and sifting through boxes until you find what I’m looking for.

In addition to the types of inquiries listed above, we often receive inquiries that we are unable to assist with. We are unable to offer help with family genealogy research or appraisals of objects, and some other questions we receive are better answered by other organizations. For these types of inquiries, I think of myself as a sort of telephone operator; even though I don’t have the answers myself, I try to connect people with other places that may.

Some of the places I frequently suggest, depending on the nature of the inquiry, are:

- Canadian Chapter of the International Society of Appraisers for appraisal requests

- City of North Battleford Historic Archives

- City of Saskatoon Archives

- Library and Archives Canada

- Moose Jaw Public Library’s archives department

- Museums Association of Saskatchewan’s ‘find a museum’ tool

- Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan

- The Reynolds Museum in Wetaskiwin, Alberta has an extensive collection of machinery manuals and catalogues

- Saskatchewan Genealogical Society

- Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre

- Saskatoon Public Library’s Local History Room

- University of Alberta’s Peel’s Prairie Provinces, especially their searchable scans of Henderson’s phone directories for various cities across Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba

- University of Saskatchewan Archives and Special Collections

From our Registrar

Assessing Artifact Significance

An important aspect of every artifact donation is the story and significance that goes along with it. As Registrar my research starts with the first conversation I have with the prospective donor. For example, a recent acquisition of cobbler tools used by Jake Marjan started with talking to the family, learning about Jake, his role in the community, his shoe repair shop and how he used his tools. Once this information was in place, I then researched our own Collection to see if we had similar artifacts and stories already. I also rely on books, newspapers and other resources to better understand the artifacts offered, the stories associated with them and their significance to Saskatchewan’s history. This all helps me to assess the offer and determine if it should be reviewed by our Curatorial Committee for acquisition, and in this case, it did!

From our Collections Manager

Understanding 75 Years of Building the WDM Collection

Some of my work relies on research to help understand our artifact collection and how it has developed after more than 75 years of collecting at the WDM. This information helps us to set priorities in collections management. For example, an ongoing project at the WDM has been to assess automobiles and trucks manufactured in the 1920s. About 10 years ago, an earlier cohort of WDM staff conducted extensive research to confirm the make and model of these vehicles and their general physical condition. They found extensive overrepresentation of 1920s vehicles, with more than 75 in the collection!

Building on that information, I researched general trends in personal vehicle ownership in Canada, which experienced a boom in the 1920s due to mass production and increased affordability and access, with Canada becoming a major manufacturer. Saskatchewan had one of the highest rates of per capita ownership. Archival materials in WDM artifact files show that automobiles and trucks were once a priority category in the WDM’s collecting efforts, with many being collected in the 1950s when these vehicles would have still been readily available but had reached the end of their useful life and were beginning to disappear. Archival letters in some artifact files show that the WDM had planned to restore all vehicles collected with the hope that someday, future funding would make this possible – a dream that would not come to pass. This information helps to take a step back and understand why so many 1920s vehicles were collected by the WDM in its early years, providing valuable information when planning for the future.

From our Collections Care Specialist

Keeping Safe with Hazardous Artifacts

Preserving artifacts is the main part of my role, but so is ensuring the artifacts are not hazardous to those of us handling them. I often do research into the manufacture, material type and ingredients in artifacts, as they could contain expected (or unexpected) toxic hazards. Asbestos, mercury, lead and arsenic are examples of generally known artifact hazards, but everyday household, hobby and pharmaceutical products can also be hazardous if their labelling did not include the listed hazards or provide proper warning. This can be an issue with older products, one reason being that WHMIS (Workplace Hazardous Materials information System) and MSDS (Materials Safety Data Sheets) were introduced in Canada in 1988. Any products made before then do not have the standardized hazard pictorials that we are familiar with today. Products that could be benign may be harboring a hazard not identified on the packaging. Or, products may contain a hazard that was treated as negligible, but today would be classified as a controlled substance or health hazard.

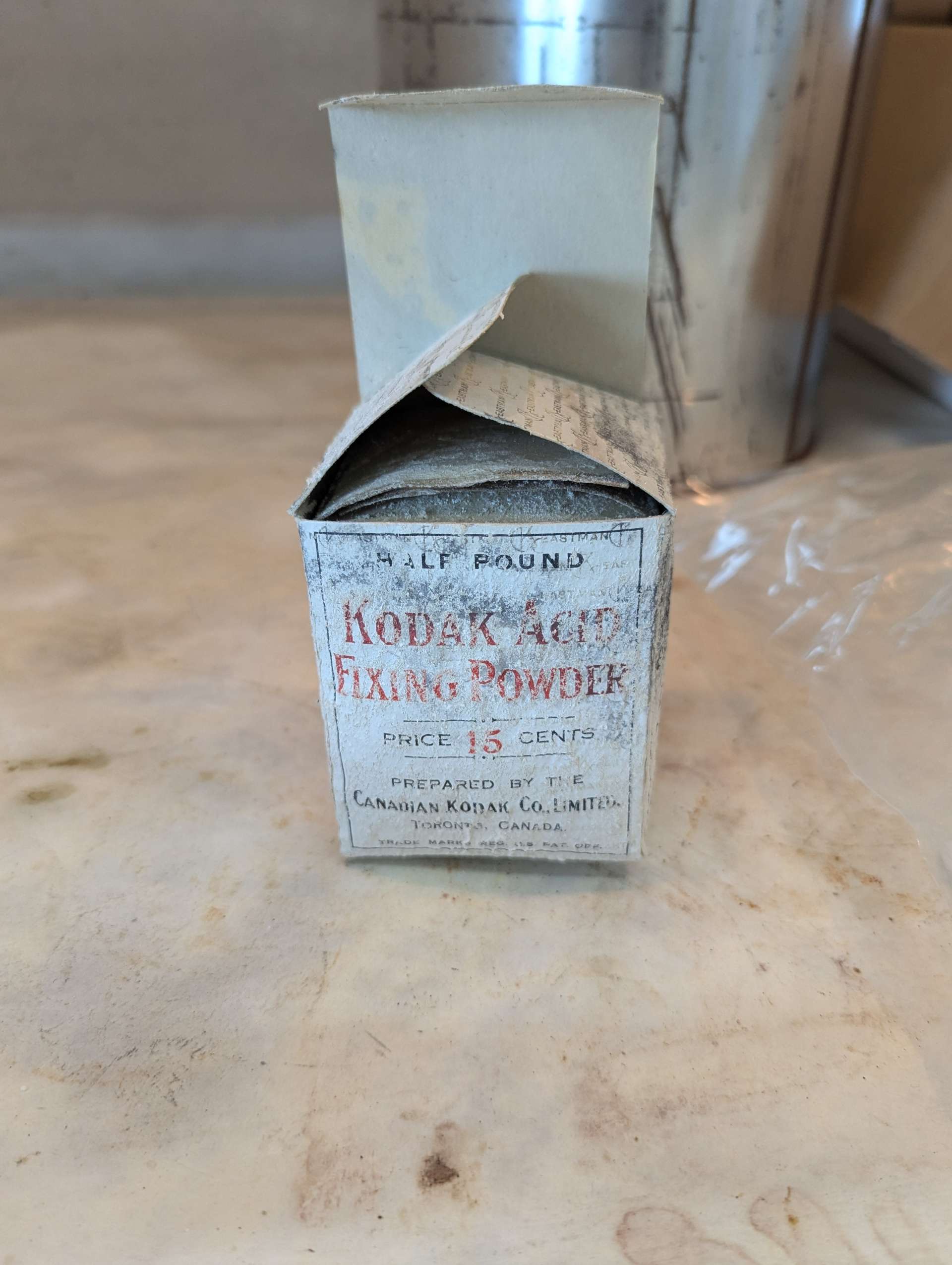

Recently, a Kodak film processing set (WDM-1991-S-38, c. 1940s) in storage was inventoried. In it, a container of acid fixing powder was partially opened and had spread onto other artifacts. No hazard labels or ingredients were listed on the container, and an opened box of mystery powder is never good! The product was too old to have a MSDS, but as Kodak is still a thriving company today I was able to find the MSDS for the modern fixing powder and get a general idea of the ingredients, which included: sodium thiosulfate, aluminum ammonium sulfate dodecahydrate, sodium acetate, disodium disulphite, diboron trioxide, borax pentahydrate, trisodium citrate dihydrate and citric acid. The mixture causes skin, eye and respiratory irritation, can damage fertility, and cause damage to organs through prolonged exposure.

Although these are dangerous, thankfully the artifact could be handled with standard PPE – nitrile gloves, an N95 dust mask and safety goggles. The artifact was stored in a polypropylene bag with a hazard label attached, and the artifacts covered in the fixing powder were cleaned. Securing this and other artifacts like this in our collection storage areas as part of our ongoing hazards assessment work, will prevent injuries and preserve the artifact safely.

From our Collections Coordinator

Careful Deaccessioning

It may at first seem counterintuitive to non-museum professionals, but deaccessioning – the process by which artifacts are removed from the permanent collection – is a critical part of maintaining a healthy, sustainable and relevant artifact collection. For an artifact to be deaccessioned, it must go through a rigorous research and assessment process. Part of my job is to use a rubric in the WDM’s Collection Development Plan to do the initial assessment of any artifact being considered for deaccessioning. The rubric includes categories related to historical significance, artistic and aesthetic significance, scientific significance, social and spiritual significance, provenance, representativeness in the collection, rarity outside the collection, impact as an exhibit, diversity and inclusion, as well as a section related to Indigenous significance.

The appearance of an artifact can often be misleading for how high I think it may score on the rubric, and the results of scoring an artifact often requires careful analysis. An artifact may be ordinary at first glance (often the case), but upon a closer inspection it can reveal a rich history. A good example of this is a set of chairs from the Star Café in Marcelin, Saskatchewan (WDM-2002-S-864). As I read through the artifact file, I saw that these chairs were part of a larger history of Chinese immigrants in Saskatchewan, through the family histories of the Howe family. These were retained in the Collection as they help illustrate and animate this important part of Saskatchewan’s diverse history.

Even though most of the artifacts that I assess do not have a detailed history, they all receive the same level of research in the deaccessioning process. Much of the time, the artifact files contain little to no provenance. Even if the only piece of information associated with the artifact is a name, it is sometimes not the individual who owned the artifact, but simply the person who brought it to the museum for donation. Some of the sources that are used to research the artifact and donor, are: newspapers.com, Canadian Museum of History database, ROM database, Region of Waterloo Museums Database, and Artefacts Canada database. Regardless of the reason that an artifact is put forward for assessment, deaccessioning is always done with the intention that by removing unnecessary artifacts from the collection, remaining artifacts can be cared for in a way that maximizes our limited resources and fulfills the Museum’s mandate.

From our Collections Assistant

Research Surprises when Working with Museum Collections

As part of an ongoing fire code compliance project at the WDM Curatorial and Corporate Services Centre, we have been working with and relocating thousands of artifacts. Most of these have not moved locations since the WDM moved into the Curatorial and Corporate Services Centre in 1984. This has led to several interesting challenges as material is photographed, inventoried and moved. But it has also led to some thought-provoking discoveries about the history of the WDM and the province. I’ve featured these finds in two blogs – the first, about the day we discovered a set of desk drawers belonging to the WDM’s first Curator George Shepherd and the second, about researching a sensitive and sometimes controversial part of our medical past, the use of Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) in mental health treatment, upon discovering an ECT device in the artifact Collection.

This feature was compiled by Dr. Elizabeth Scott, Chief Curator – Director of Collections & Research